www.bangitout.com Jordan Hiller is taking the Essential 25 to its top ten…can you handle it??

Check his number 9 newbie, noted as one of the Jewiest Movies of the year…if not all time…

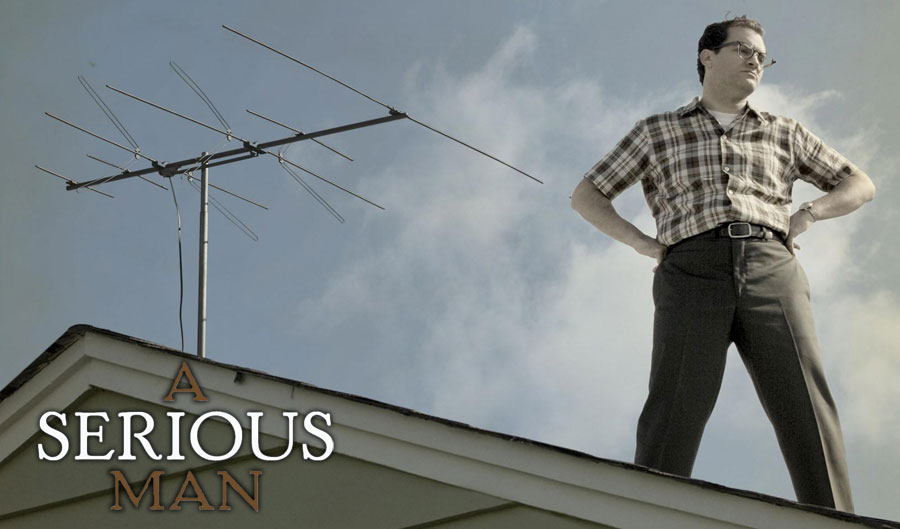

9. A Serious Man

The Coen brothers, Joel and Ethan, would not be pleased to find their latest work on a list of essential Jewish films. They do not comfortably affiliate with the religion, neither planned on attending Yom Kippur services, and both married out of the faith. Like the son of A Serious Man’s central character, the beleaguered Jewish academic Larry Gopnik (played with squirming intensity by Michael Stuhlbarg), the Coens attended Hebrew School while growing up in Minnesota and read from the Torah upon reaching Bar-Mitzvah. In the film, Hebrew School is depicted as torturous; administered by a decrepit hairy-eared Jew who drones over verb conjugations in Ivrit as the class of awkward and befuddled Jewish kids zone out. Receiving an aliyah and laining from the Torah is portrayed as harrowing and awful (though at the same time momentous and pride-worthy), so much so that toking up beforehand appears a most promising way to get through it. I asked the filmmakers of such modern classics as Blood Simple and Fargo if anything at all in their tour through Hebrew School engaged them or promoted a love or interest in Judaism. “No,” Joel was quick to respond. “Nothing,” Ethan said without hesitation. “Hebrew School was something we were forced to do,” Joel added. “Something we desperately tried to get out of, but couldn’t, for years and years and years.” As for their Bar-Mitzvah memories, both remembered the experience as being a pretty typical Conservative ceremony circa 1967. “Nothing out of the ordinary,” they commented plainly. Joel remembered that they each read from the Torah and Ethan qualified that they read, but certainly not the entire week’s portion. Ethan lost the Kiddush cup they were gifted by the Sisterhood upon the occasion; Joel still knows where his can be found. All these hazy, semi-sour, semi-nostalgic recollections and a myriad of exquisitely authentic others are incorporated into their latest film, another outstanding example of darkly surreal, tight and twisted, philosophically deft storytelling.

“We’re not trying to help anyone understand the Jewish experience,” Joel explained. “It’s just a story about community and family…and we’re trying to be specific in the telling of that story. Specificity is important.”

While Joel’s words may or may not be the whole truth, A Serious Man not only acutely conveys an abundance of data about cultural and religious Judaism, it undoubtedly will be a very different audience experience for Jews and then for everyone else. Different to a point which makes it difficult to comprehend how a non-Jewish viewer would relate to the material. It’s like trying to surmise how a non-Jew would react to a steaming bowl of chulent.

A Serious Man opens with a quote allegedly from Rashi. Receive with simplicity everything that happens to you. I mentioned to the brothers that while Rashi was a prolific commentator on Talmud and Tanach, he is not exactly a figure oft quoted. They – perhaps knowing their bluff had been called – laughed. I asked where they pulled the line from. “I honestly don’t remember,” Joel curiously admitted.

Following Rashi’s sound advice we enter a snow-filled landscape where a bearded Jew trudges back to his shtetl cabin so that he may tell his homely wife of the day’s meager affairs. The entire shtetl prologue is delivered in a vibrant, hysterical Yiddish with subtitles that scarcely do the dialogue justice (however the overall effect is entirely successful). When the man mentions to the wife that a former acquaintance assisted him on the way home, the classically Chassidic tale takes a Coenian macabre turn.

From there we leap to an unrelated 1967 Minnesota suburb and meet Larry who hopelessly treads amid turbulent waters, confronted by marriage, professional, and personal health issues so gratingly complicated and compounding that they could only exist as snares and devices brilliantly laid out in a bizarre Coen Brothers universe. His wife’s boyfriend is killing him with kindness, hugs, and pleas to be “reasonable.” His Uncle Arthur (played with pathetic aplomb by Richard Kind) is a catastrophic mess, sleeping on the Gopnik’s couch, and always hogging the bathroom. Through the presentation of these vexing developments and hurdles, A Serious Man sheds light on a series of uniquely Jewish challenges, from agunot and uniformly bad noses, to anti-Semitism and the eternal struggle to define “What Hashem wants from us?”

That last bombshell question, as Larry posits it to a community rabbi, may be at the epicenter of Larry’s quest to either become or, if he perchance is one already, remain a serious man (which very well could be the Coens’ loose translation of “mensch.”) Is a mensch someone who takes both the good and the bad in stride and on faith as Rashi suggests? Or is it someone who stands up for an ideal at all costs? Or perhaps it is someone who knows when to bend and compromise in order to maintain sanity in this world at the risk of damnation? All these are possibilities that the film presents and explores, but of course leaves as ambiguously unresolved as Kohelet before that dubious final verse.

What is most phenomenal about the construct of the film is that the Coens divide Larry’s journey into three acts (each separated by a black screen, a thunderous knock, and the name of a rabbi). Like a reverse of Dickens’ Ebenezer Scrooge, Larry visits three rabbis in an increasingly vain attempt to untangle his contracting web of tzuris. First he speaks with the gloriously young rabbinic intern in a tiny cluttered office. Rabbi Scott haplessly educates Larry about “perspective,” using the parking lot outside by way of example. If only Larry could see the parking lot for its inner magnificence and grandeur, he would better understand Hashem, Hashem’s plan, and Larry’s own place in that plan. Ironically enough, a heart-wrenching scene toward the end of the movie where Uncle Arthur confesses seismic jealousy of Larry’s life, actually lends the rabbinic novice some belated credibility.

Larry next sits down in a modern, generously proportioned, bright room with Rabbi Nachtner, the Conservative shul’s genial, comfortably tenured spiritual leader. Although a remarkable (supposedly true) anecdote is rendered regarding a Jewish dentist who finds a startling Hebrew word on the backside of a gentile patient’s teeth, the story proves irrelevant to Larry’s situation and Rabbi Nachtner has been at the job so long he has lost any ability to be genuinely moved or inspired and certainly cannot move or inspire others. The last Rabbi, Marshak, ancient and seen groaning whispers from his vast hardwood study where treasures and mysteries are piled from floor to ceiling, refuses Larry admittance because, as the Rabbi’s coarse secretary asserts, he is busy thinking. Larry’s son later is granted audience with Rabbi Marshak upon his Bar Mitzvah and the sage’s unearthly wisdom is somewhat stunningly revealed.

“There actually was a rabbi in our town,” Ethan recalled, grinning, “who wasn’t actually our rabbi, but who met the kids after their Bar Mitzvah…and he was this sphinx-like Wizard of Oz guy.” According to Ethan, The Coen’s rabbi, Rabbi Arnold Goodman, ended his sermon with the same bracha each week; a detail evoked in Rabbi Nachtner’s address over the Bar-Mitzvah Shabbos.

When asked about how much of the film is reminiscent of their growing up, Joel answered that for a while they both thought it would be interesting to write something set in their childhood community. They also thought it would be fascinating to create something that showcased both the Jewish cantorial, liturgical music familiar to them from home and shul, with the rock music they listened to with their friends. In the film, Jefferson Airplane and Yossele Rosenblatt are given equal face time.

“Midwestern Jews are very different from city Jews like in New York and L.A.,” Joel insisted. “This film is not about just a Jewish community. It’s geographically specific.”

And it is. Although it seems like everyone important in Larry’s world is identifiably Jewish, the audience still gets the sense that these odd, intellectual, well meaning but inescapably off-putting citizens are transient outsiders. That the community's days are numbered.

“The Jews originally were living downtown and in the center of the city,” Ethan explained, “but began moving to the suburbs. Our community was predominantly not Jewish.”

By delving back into their past, Joel and Ethan skillfully and entertainingly capture a tumultuous time when both the Midwestern Jewish community and the concept of America as a whole drastically shifted. Societal norms changed forever and did so with frightening alacrity. And somewhere in the chaos of that era, between the rigors of Hebrew School and the Siren’s call of a cultural revolution, the Coen brothers, two of the greatest filmmakers of all time, were formed, spread their wings, and flew.