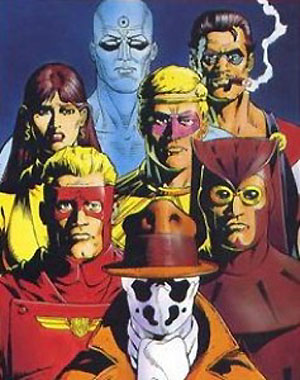

atching the Watchmen take their eye popping leap from the elegant pages of a revered graphic novel to the clamorous grandiosity of the big screen, I thought a lot about Alan Moore. Moore, that wild bearded mountain-man glaring up menacingly from the back cover of most editions of DC’s 1986 comic mini-series, so readily exemplifies that age-old correlation between madness and genius. He is not a cog in anyone’s corporate machine or a nine to five working scribe trying to make a living in the comics biz. He is an awesomely talented storyteller with the appearance, confidence, and perhaps transcendent awareness of a raving prophet. Two of his creations have been adapted by Hollywood prior to Watchmen, and just as Moore dissociated himself from The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and V for Vendetta, so too now with his most beloved and renowned achievement. He has signed a waiver with Warner Bros., refusing to accept a penny of Watchmen’s royalties. He has been burned and abused in the past by studios and has learned that no matter the intentions, loyalty, or respect given by those promising to handle his baby with care, what ends up on screen is a shameful shadow of the original. And it’s not like Moore distanced himself or announced his disgust after seeing the Zack Snyder directed result. He refused to participate from the outset, almost predicting an inevitable conclusion. In that sense he has become much like his own offspring, Watchmen’s indestructible Doctor Manhattan, a supreme being with G-d-like powers (fighting alongside and against mere mortals) who sees the past and future woven seamlessly into the present. Doctor Manhattan, a human in origin, but altered after a nuclear accident, represents the most phenomenal presence in Watchmen – a tale of costumed heroes in a powder keg world out looking for a jolt. The bald, blue, glowing, well-meaning philosopher is constantly conflicted by his human foundation set at odds with his divine abilities. So Moore, the divine artist, foretells his disappointment at the hands of distracted (“$”) filmmakers and shutters himself from the remote possibility that Watchmen will emerge whole and pure. He, like Doctor Manhattan, removes himself from the situation to avoid the anguish and folly of an uncomfortable reality.

Toward the end of Watchmen, Doctor Manhattan, who has fled to Mars to perhaps begin a new and better civilization than the one he left behind, is taught something by his human “girlfriend” and realizes that he was wrong, that his distance was wrong, perhaps that his self-assured arrogance was wrong. Moore may want to take a lesson and at least view the new Watchmen movie (something he declared he would not do), because while it never recreates the chilling magic of his novel, it is humbly faithful and a wonder on its own terms. At the very least, the inventive opening credit sequence, backed by a Bob Dylan classic, is shiver inducing (especially to those just settling in who recognize the references). The rest of the movie…has its moments. Visually stunning with some radical camera tricks, it suffers from poor character development and a lack of fluidity. It feels very much like a progression of scenes as opposed to a linear story that matters. The surprise finale, unlike in the novel, is inexplicably telegraphed early on. Regardless, the visual marvels along with some strong performances (like Jackie Earle Haley’s dead on Rorschach) can satisfy a casual moviegoer.

There are only two elements that can wholly spoil the intense and bizarre experience (well, three, if you can’t sit in a movie theatre for nearly three hours). One is the over the top nudity, including full frontal male on a number of occasions. Not to sound prudish, but it’s one thing to see a rough drawing of the male anatomy on the pages of a comic, it is another to see a fully formed, quite girth-full member dangling in the breeze. I could understand wanting to be true to the novel, but why not be tactfully true? One might say it is unfair to pick on the skin when the film portrays astonishingly gory moments of violence. Well, while both are gratuitously used to shock and drag us into the “serious” and “bleak” atmosphere that Moore, along with artist Dave Gibbons, created two decades ago, spurting blood and the crackling of bones sort of flow with the dark territory of Watchmen; an elongated love scene does not (though the novel, again, does not shy away from frank sexuality, or any other sinister or brutal aspect of our existence for that matter).

The other and more overwhelming issue is that if you are familiar with and beholden to the graphic novel, much of the celluloid depiction will come as an affront. Snyder’s Watchmen, though imaginatively filmed and coolly crafted, is endlessly exposed to critique from fans. Why? Partly because with only the rarest of exceptions can a movie improve upon a book. It’s simply a matter of narrative dynamics. A story cannot be told better by manipulating and condensing it and leaving the characters in the hands of fallible actors when a reader’s imagination forms personalities with such precision. The pursuit is like trying to clone an organism from a set of genes, yet somehow have the replica improve upon its source material. The clone can be only as good, and only then if all goes flawlessly well during the scientific process; but the chances of an unforeseen glitch are more than likely. So translational error is always a factor in these kinds of precocious (some might forgivingly call it ambitious) adaptations.

But mainly the experiment fails because you can’t please the rabid, fawning masses, especially when Watchmen’s band of misfit adventurers have been given so long to become integrated into their dreams, both the night and day varieties. Every casting choice and editing decision sparks an infinite number of arguments and fervent protests (and there are undoubtedly those here as well – the difficult to bear Malin Akerman as Silk Spectre II and the too youthful and meek Matthew Goode as Ozymandias are the obvious indiscretions).

If this film were released in 2009 and called Watchmen and it was based on no previous work, maybe audiences and critics would be heralding it as a brilliant masterstroke. But it’s not. It is relegated to a fate of being forever compared to something actually brilliant and the comparison can only wound and torment it. Like on American Idol, when the judges admonish a contestant for choosing a certain song because it is “untouchable,” they are expressing that the young singer, no matter how well they sang or performed, could never derive benefit by choosing such a song. Because it will always be identified with its most ideal and exceptional first incarnation.

Basically, with Watchmen, the filmmakers could not win. By committing to the plan, they conceded the battle and marched on. They unabashedly declared to the devoted throngs, “We Shall Fail You!” The agenda then became (whether consciously or otherwise) not to match Watchmen’s caliber of excellence, but to animate the voiceless (which is always an irresistible Hollywood impulse), and – this is the interesting focal point– to bring the graphic novel to a wider audience. Because there are some who read books and avoid movies and there are many who watch movies and avoid books, and there are plenty who enjoy both. Comic books, however, despite their definitional capacity to entertain all camps, seem to land somewhere beyond the typical entertainment consumer’s radar. Comic books, if attentively placed on the book/movie spectrum would naturally gravitate toward the movie end because of their visual components, yet they can satisfy a reader and are brief and portable (if you can believe it, movies used to not be portable…I swear.) My awkwardly put position is that technically speaking, more people should be reading Watchmen and those of its grade. Its time to fully remove the stigma of graphic novels (or “glorified comic books”) and projects like the Watchmen movie go a long way in doing that.

Full disclosure: I had never heard of Watchmen until the buzz began about the motion picture version, so, last summer, I bought a copy and read it in a few days. To call the experience thrilling and troubling and intoxicating would be an understatement. It is an all-consuming, delightful and disturbing miracle of human intellect and potential. The blending of labyrinthine story, surreal politics, social comment, human condition, uncomplicated but moving art, and deft philosophy is a feast for both the heart and mind. Can the same be said about Snyder’s movie? Of course not. Could anyone have reasonably expected it to? Not reasonably. The most enjoyable aspect of the movie for me was being reminded of my time with the book. As a whole, Watchmen achieves a very impressive level of skillfully assembled popular entertainment. It daringly captures on film what was once believed to be unfilmable. That accomplishment aside, it is difficult to imagine the underlying reason for attempting the exercise without coming up with “$.” However, Watchmen has already been proven to have brought about a very substantial and imperative side effect – myself being an example. People – all kinds of people across the various demographics – are buying and reading Moore’s 1986 Watchmen. Folks of all ages are currently hating The Comedian, dissecting Nite Owl II, lusting after Sally Jupiter in her prime, being perplexed by Ozymandias, pitying Rorschach, and departing Earth for Mars with a naked, blue, chrome-domed G-d manufactured in a lab. These introductions alone, I can honestly say, puts a smile on my face.