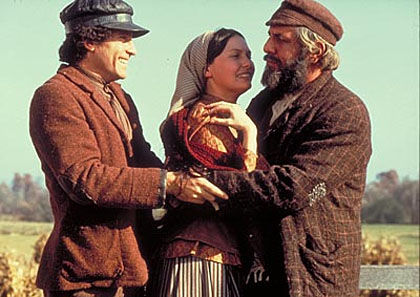

AND THE NUMBER #1 ESSENTIAL JEWISH MOVIE IS…..drum roll please

#1. Fiddler on the Roof

As the durable Joseph Stein stage play – originally choreographed by the legendary Jerome Robbins and based on the stories of Shalom Aleichem – sings, dances, struts, and mopes its away across the screen in Norman Jewison’s faithful 1971 version (seven years after the musical’s Broadway debut), it becomes both heartening and discouraging that so much about Jewish life remains unchanged. Whether in 1905 Anatevka, Russia or Cedarhurst, Long Island in 2010, our joys, hopes, sorrows, and fears fall into an unmistakable pattern that cannot be mended, erased, or transformed by progress, industrialization, technology, or Costco. Our fathers are questioning but confident and sometimes raging Tevyes. Our mothers are protective, powerful, neurotic Goldes. Our children are as challengingly diverse and inexplicable as Hodel, Tzeitel, and Chava. We are products and embodiments of them all. And our Jewish existences, at times a struggle, at other times a fanciful breeze, are as somberly beautiful as the notes being struck by a precariously positioned fiddler on a roof. Because like the fiddler who dwells in the moment and is pleased by his bittersweet melody, we know that a devastating fall is as imminently feasible as the ability to keep on playing.

Like all great shows, Fiddler opens with a showstopper. Through Tradition, a simple upbeat song about the comfortable yet confining roles we are obliged to slip into based on our gender and position in the family, the audience is introduced to the blueprint (perhaps the secret) of Jewish survival and vitality. We are followers of traditions ancient, immovable, and divine. As believers in (or hapless deferrers to) a living Torah that lays the foundation while allowing for modifications that adapt to social, psychological, and economic evolutions in man, Jews have a built in mechanism to keep things moving forward without ever disregarding old ways. Traditions are as much our prisons as they are our life blood.

And so it goes throughout the film. With each musical number, another integral and eternal aspect of Judaism is pondered, explored, and expressed with passionate flourishes. With Matchmaker, the so-called shidduch crisis comes to mind. To Life evokes our most elemental prayer in this world; to recognize that every organic instant is a nes and cause for celebration. But likely the most memorable tune and performance from the entire nearly three hour epic is Israeli actor Chaim Topol as Tevye’s rendition of If I Were a Rich Man. No single song encapsulates the wild tempest of the Jewish experience better. Not many compositions can at the same time convey a deep longing for God, a saintly faith-based approach, a melancholy sort of optimism, and a turgid existential philosophy, all while being essentially about a pitiable monetary necessity. Well, not many people are Jews. And Jews comprehend Reb Tevye from cap to boot. We perceive that strange desire for the staircase that goes nowhere just for show while at the same time truly believing that spirituality matters above all. What could be more profoundly affecting to us than the lyrics:

If I were rich, I'd have the time that I lack to sit in the synagogue and pray. And maybe have a seat by the Eastern wall. And I'd discuss the holy books with the learned men, several hours every day. That would be the sweetest thing of all.

It is the classic Jewish contradiction that we witness time and time again. Our communities are consistently marked by staggering materialism and financial ambition going hand in hand with morals and ethics (and even insatiable desires) that urge modesty, piety, holiness, and the concept that parnasah is only a means to an end.

If I Were a Rich Man also provides Tevye, a man constantly under the strains of domestic and political burdens, a manner in which to cry out to Hashem without conforming to the limitations of mere words. As Topol belts out his painful final Ya ha deedle deedle, his voice cracks and we sense the generational misery of our ancestors who suffered terribly in lands not their own. We emulate this form of expression many times throughout our lives in shadowy candlelit rooms, perhaps after a moving tale of emunah and bitachon.

Because the songs in Fiddler on the Roof that are most associated with it are on the cheerful, toe tapping side, it struck me upon reevaluating the film how thoroughly depressing it all is. Tevye, his family, and his fellow residents of Anatevka are allowed some bursts of simcha in life, but all good things are short lived, and more things are bad than good, and when things are good they are only semi-good, and when they are bad they are truly awful.

Hodel marries a pathetic tailor instead of a rich butcher and the tailor eventually buys a sowing machine. That’s the good news. The bad news: Tzeitel and Chava stray from Tevye’s derech and clash with tradition, the youngest daughter in a way that shatters a Jewish parent’s hopes beyond imagination. And after all these terrible trials, the entire congregation of Anatevka’s Jews are thrown out and sent wandering for typical anti-Semitic, bureaucratic reasons. The final scene depicts a herd of dusty Jews, helplessly moving on, all their belongings being dragged and schlepped to an unknown destination.

And as comfortable as we are with our iPhones, Monday Night Football, and enormous kosher supermarkets, don’t we envision ourselves often on that road? One minute we are dropping the kids off at overpriced school in a brand new Honda Odyssey, and the next we are drifting aimlessly across a barren landscape, telling our children it will be okay, hoping someone will take us in, regretting so much that we abandoned and neglected when times were good.

And even in those ominous prophecies we know that the lean times, the desperate times, the harsh times, will come and go. Somehow, someway, the Jews of Anatevka will settle down in Israel or America and build new lives, and new shuls, mikvas, butcher and tailor shops. We know this because, like the master Tevye, we understand how to communicate with our Father and Creator in heaven. Jews feel close enough to God to argue with Him, complain, beseech, and curse Him as often as they offer blessings, thanks, and praise.

A Jewish life is undoubtedly a balancing act where one must always be weighing both sides. The trick is to be wary of all possibilities, clutch the tradition mightily, and somehow with good mazal, remain securely on the roof.