Movies of 2011 Recap PART 2: A Year in Girl Power

(Part 1 of the 2011 Recap can be found here)

Suffrage sounds every bit as dusty as its one hundred plus years. Feminism is a bit better, but will never shake its angry, tumultuous 60's vibe. Girl Power might be a relic of the Spice Girls ruled final gasp of the 20th century, but at least it speaks of women having already arrived, beginning to explore their independence, and enjoying some guilt free fun.

One place where the movement always seemed to lag was Hollywood, where raunchy, infantile comedies, testosterone-fueled action flicks, and the objectification of gorgeous women by mostly male directors and producers, held its firm footing. To throw out a modern day example: One will not find a single male movie star that can be compared to Megan Fox and the undignified fame that she enjoys, yet there are hundreds of undiscovered “actresses” ready to slip into her tube top and stilettos.

Whether it received the headlines it deserved or not, 2011 was a banner year for challenging, diverse female leads. While past years felt like the Academy struggled to fill the five nominee slate for Best Actress (Sandra Bullock actually won for The Blindside two years ago, and, last year, Black Swan’s Natalie Portman faced no real competition), this winter is going to be a dogfight.

And it was not only a strong year for women carrying films that valued substance over skin and sensuality, but the stories these films told were about women being supported and understood specifically by other women; with the boorish, misogynist men looking on clueless, spineless, or heartless from the sidelines.

In Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia and Sean Durkin’s Martha Marcy May Marlene we are introduced to two young women evidently damaged and in the wake of some anonymous trauma. We cannot be sure as to the extent or details of their individual experiences – and to be sure they are vastly different – but their support systems, however ineffective, are the same. When these reeling, aching women focus enough to flee the bad in their lives and seek to perhaps tame inner demons, they run to family, and in particular, to sisters. The use of a sister’s home and embrace to signify safe haven is the comforting, pleasant similarity between the two excellent films. There is another parallel theme darkly building within each, but that commonality is murky, dire, and far thornier.

In Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia and Sean Durkin’s Martha Marcy May Marlene we are introduced to two young women evidently damaged and in the wake of some anonymous trauma. We cannot be sure as to the extent or details of their individual experiences – and to be sure they are vastly different – but their support systems, however ineffective, are the same. When these reeling, aching women focus enough to flee the bad in their lives and seek to perhaps tame inner demons, they run to family, and in particular, to sisters. The use of a sister’s home and embrace to signify safe haven is the comforting, pleasant similarity between the two excellent films. There is another parallel theme darkly building within each, but that commonality is murky, dire, and far thornier.

The relational dynamic between sisters is not one I can speak of personally, though I have sufficiently witnessed the exceptional power of sisterly devotion second hand. There may not be a more intimate, impenetrable bond on Earth.

And speaking of Earth, Melancholia uses the ending of life on our home planet to study two women (two sisters) and their choices leading up to the cataclysmic event. Both women, in their own way, perceive the inevitable approach of mortal disaster, but one welcomes it and the other denies and rejects it.

Kirsten Dunst, in a role that brilliantly contrasts her celebrated youthful exuberance (we are a long way from Bring It On), plays Justine, a self-sabotaging, masochistic bride consumed by what at first appears to be depression, but later transitions into a more troubling, perhaps madder, disposition. In an alarming, yet eye opening twist, Von Trier indicates that Justine’s unconquerable misery may lie in her keen understanding of the pending destruction of Earth; the result of a hurtling rogue planet (unsubtly tagged Melancholia) on a collision course. That Justine’s inability to find (or, rather, accept) happiness is simply in direct reaction to her unbearable knowledge of immediate, unavoidable doom. In that sense, Justine’s objectively insane behavior becomes completely comprehensible. Those pretending that there will be a tomorrow and making breakfast plans are the fools. Why should a bride remain composed and docile at her extravagant, fantasy wedding when the concepts of marriage, commitment, and romantic contentment are mere hollow, temporal sentiments awaiting evisceration?

Justine expresses her founded pessimism (a trait/curse she may have inherited from her mother) by inciting those around her with sinister bursts one moment and sincere compassion the next. All the while, Justine’s sister, Claire (intense Charlotte Gainsbourg), tries desperately to care for her, but Claire is secretly facing her own crisis: How does one live in the shadow of imminent death? How does one maintain rationality in a world where the impossible may happen (and when one has children to pacify and explain things to)? Essentially, the question may be theologized: How does one survive in a world where a merciful, attentive God does not exist?

Von Trier has already established the reputation as a provocateur (2009’s Antichrist); an unnerving filmmaker challenging audiences with festering itches that refuse to be scratched. Melancholia takes great pleasure in distressing its audience with ugly, harrowing imagery and behavior, but, more often that not, Von Trier’s film is an exhibition of life’s beauty and the shame it would be to watch it burn. With Richard Wagner’s prelude to Tristan and Isolde accompanying the chilling cinematography of Manuel Albert Claro, Melancholia achieves a level of art rarely witnessed in narrative film (and surely not an American production, which Melancholia is not).

Does Von Trier sexualize Justine/Dunst gratuitously? He does; at first by having his ingénue wear a cleavage accentuating wedding gown, then by showing her commit what amounts to a sexual assault, and finally (most egregiously) as Justine is discovered completely nude, in full pin-up centerfold mode, sprawled outdoors, eroticizing the pink glimmering orb promising her demise. This is not to say that Dunst has anything to be ashamed of. On the contrary, her performance is pitch perfect and redefining, and should revive her slumping career. Von Trier, with a symbol of purity such as Dunst at his disposal, evidently could not resist the urge.

Mr. Durkin confronted a similar temptation when given the demure Elizabeth Olson to direct in his breakthrough effort Martha Marcy May Marlene. Like Dunst, the Olson sisters (Mary Kate and Ashley of course) were child actors. We’ve watched all three grow from cute girls to sexy young women, from adorable to desirable. It is certainly an awkward transition to admit or discuss, but not one we can ignore, especially since filmmakers are strategically using our image and impression of these women to obtain a unique result. Although Olson is not an “Olson sister” in the classic sense, she does carry that pristine air of untouchability due to the family connection. We are protective and covetous of her by extension. Moreover, her character’s innocence and neediness combined with the forbidden element of the Olson pedigree creates the perfect storm of titillation.

Mr. Durkin confronted a similar temptation when given the demure Elizabeth Olson to direct in his breakthrough effort Martha Marcy May Marlene. Like Dunst, the Olson sisters (Mary Kate and Ashley of course) were child actors. We’ve watched all three grow from cute girls to sexy young women, from adorable to desirable. It is certainly an awkward transition to admit or discuss, but not one we can ignore, especially since filmmakers are strategically using our image and impression of these women to obtain a unique result. Although Olson is not an “Olson sister” in the classic sense, she does carry that pristine air of untouchability due to the family connection. We are protective and covetous of her by extension. Moreover, her character’s innocence and neediness combined with the forbidden element of the Olson pedigree creates the perfect storm of titillation. Durkin uses the actress and her aura to tell the story of a girl named Martha ensnared in the clutches of a dangerous cult (where she is renamed by the manipulative cult leader, Patrick, played with reptilian calm by John Hawkes) and, what’s worse, Martha becomes inculcated with the cult mindset. When she finally learns too much (and what Durkin relies upon to depict “too much” is more self-servingly graphic than believable) Martha attempts to find refuge in her estranged sister, Lucy’s (Sarah Paulson) home. The problem then being that her time with the group has left her psychologically wounded, socially demented, and in fact a safety hazard. Durkin and editor Zachary Stuart-Pontier do a tremendous job of cross cutting between Martha’s present – the rehabilitation with Lucy – and flashbacks where the true sadistic nature of the cult is progressively being revealed. What could have come off as a gimmick winds up an essential, insightful manner of storytelling.

Much like Justine, Martha resists and fails to properly appreciate her sister’s intervention and likely for the same reason. No matter the loyalty and earnest intentions, the problems Martha and Justine struggle with are too profound for ordinary remedies. Lucy and Claire can only offer sympathy, patience, and the lap of luxury.

Intriguingly, both Melancholia and Martha Marcy rely on a formula that has the protagonist’s sister married to very wealthy men of questionable motivations. The men in both these movies are powerful and insist on pulling the strings. Martha and Justine are brutal, yes, but they also display an uninhibited vitality that lies in stark contrast to the cold, calculated, polished silver emotions of their savior sister. Lucy and Claire both love and trust their husbands, but we learn that men have devious hidden agendas. These films slyly suggest that men are treacherous, with their boundless confidence and obsession with control.

Does Durkin – a man to be sure – compel Martha/Olson to compromise her modesty? He does; as Martha is a sexual plaything in the context of the cult and certainly a voluptuous treat set to frustrate Lucy’s phony husband. The argument could even be made that Durkin’s treatment of Olson precisely reflects Patrick’s treatment of Martha. Ms. Olson is a young actress desperate to enter the cult of Hollywood; to escape and separate herself from the predominance of her successful, affluent sister(s). And, apparently, to do so, she must play the game. As much as Olson’s incendiary performance reveals her individualism and true power as a career woman and artist, it also exposes her as an enticing dish served up.

Then there is the curious case of Albert Nobbs. A movie with the look and texture of a fable, it is inarguably an achievement of performance and craft, but Nobbs remains an enigma in that its direction and goal is undeterminable. The difficulty is the eponymous central character herself.

In Rodrigo Garcia’s film based on George Moore’s short story, Albert is a stunted, under-developed woman living as a man in 19th century Ireland. She hides, she frets, she deludes, minimizes, and constricts every element of her inner and outer self. Albert’s dream is to save enough shillings to open a small tobacco shop. Beyond that modest motive, we never discover much else about her personal philosophy or experience (only that she had some rough times in her female living days). We know that she is not a feminist, or a schemer necessarily, or a blatant homosexual, or a transvestite exactly, or even an androgynous experiment. She presumably is just a dazed simpleton in need of good advice. Just as we are about to see Albert metamorphose into his/her butterfly – due to a “chance” encounter with her externalized ideal self – and become something more than a nebbish servant with a bad haircut, the story takes a sudden, convenient macabre turn and amputates whatever engaging adventure was left to pursue. Although one cannot question the quality of performances here, with Glenn Close Mia Wasikowska, and Janet McTeer leading the way, Albert Nobbs suffers for lack of breadth and vision. It’s not that Nobbs is inherently insufficient; it’s that it wastes the potential for so much more. Based on the truly frightening appearance of Albert, I was hoping for a The Talented Mr. Ripleyesque tale of deception and murder. Nobbs actually feels like a short story stretched out to make a movie when we would have preferred a full length novel cut down.

In Rodrigo Garcia’s film based on George Moore’s short story, Albert is a stunted, under-developed woman living as a man in 19th century Ireland. She hides, she frets, she deludes, minimizes, and constricts every element of her inner and outer self. Albert’s dream is to save enough shillings to open a small tobacco shop. Beyond that modest motive, we never discover much else about her personal philosophy or experience (only that she had some rough times in her female living days). We know that she is not a feminist, or a schemer necessarily, or a blatant homosexual, or a transvestite exactly, or even an androgynous experiment. She presumably is just a dazed simpleton in need of good advice. Just as we are about to see Albert metamorphose into his/her butterfly – due to a “chance” encounter with her externalized ideal self – and become something more than a nebbish servant with a bad haircut, the story takes a sudden, convenient macabre turn and amputates whatever engaging adventure was left to pursue. Although one cannot question the quality of performances here, with Glenn Close Mia Wasikowska, and Janet McTeer leading the way, Albert Nobbs suffers for lack of breadth and vision. It’s not that Nobbs is inherently insufficient; it’s that it wastes the potential for so much more. Based on the truly frightening appearance of Albert, I was hoping for a The Talented Mr. Ripleyesque tale of deception and murder. Nobbs actually feels like a short story stretched out to make a movie when we would have preferred a full length novel cut down. What we learn mostly about – and it is interesting enough – is the class system of the time, the aspirations of the poor, the intimacy of the commoners in the workplace in juxtaposition to the rigid social elite (a matter well covered by The Remains of the Day). The screenplay, written in part by Ms. Close, has very little to say about what it means to be a woman compelled to live as man. The fact is, in a post Boys Don’t Cry world, where that particular issue was dealt with so viscerally, there might not be much to add to the conversation.

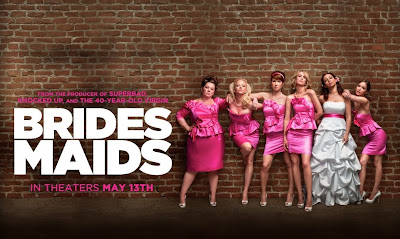

If there is one genuine Girl Power movie in the bunch, where women rule and treat the men involved like victimized eye candy, it is Paul Feig’s Bridesmaids. The film was promoted as a raucous comedy and described as The Hangover for women (and came with a great poster showing six cool, funny, hot women posing up against a brick wall), but such comparisons do not serve Bridesmaids well. Whether it says something incisive about female friends and their inability to truly feel comfortable with one another and rise above petty jealousies and competition, Bridesmaids never achieves the wolf pack camaraderie that The Hangover executes so naturally.

If there is one genuine Girl Power movie in the bunch, where women rule and treat the men involved like victimized eye candy, it is Paul Feig’s Bridesmaids. The film was promoted as a raucous comedy and described as The Hangover for women (and came with a great poster showing six cool, funny, hot women posing up against a brick wall), but such comparisons do not serve Bridesmaids well. Whether it says something incisive about female friends and their inability to truly feel comfortable with one another and rise above petty jealousies and competition, Bridesmaids never achieves the wolf pack camaraderie that The Hangover executes so naturally.

Not only does Bridesmaids not provide a linear journey for the six women in the ads to share, but even when they are together, Kristen Wiig, Maya Rudolph, Rose Byrne and the crew never feel like they are part of the same story, let alone on the same page. Not that Bridesmaids needs to be The Hangover…but it would have been better if it were.

The screenplay by Wiig feels like a collage of her SNL characters amid rejected (however amusing) skits inserted into a stilted narrative. The highlight of the movie happens to arrive when the women are finally allowed to mix it up and play off each other (the scene hysterically combines bad Brazilian food and dress shopping). But the bachelorette party that should have followed (yes, in Vegas) and which was teased in the previews, is cut down in stride. Instead, the movie focuses on Wiig, and though she is talented and has an impeccable comic sense, her character is unlikeable and somewhat repellant. We spend a lot of wasted comedy time trying to watch her close the deal with a good man (a local traffic cop). Is Bridesmaids a fun, funny movie? Yes it is. Does it allow the ladies to strut their stuff and take ownership of a male dominated genre? Sure. But this is still Hollywood, and we’re just not all the way there quite yet.