2011 Movie Recap: Part 5 of 5: A Year in Thrills

In a sense, sticking a movie in the Suspense or Thriller section should be outlawed (and with Blockbuster gone, we are practically there). The description clumsily presumes the category is one with unique attributes when really it promotes qualities that should be prerequisite. Because every story worth telling or following needs to create audience suspense and must be, relative to normal, non-ticket/purchase-needing life experiences, thrilling.

However, we are not going to pretend we don’t understand as to what the definition alludes. Within this loosely understood genre of movies, filmmakers are not merely looking to arouse typical or even heightened emotions and reactions. If produced correctly, Thrillers have one undeniable agenda: To unreasonably manipulate our anxieties and fears; to sadistically tease and tweak our nerves, brains, and sweat glands; to engage our panic reflex as often and as violently as possible; to keep us squirming in our seats and leave us breathless by the credits; to make the movie theatre as claustrophobic and uncomfortable as the inside of a pine box.

However, we are not going to pretend we don’t understand as to what the definition alludes. Within this loosely understood genre of movies, filmmakers are not merely looking to arouse typical or even heightened emotions and reactions. If produced correctly, Thrillers have one undeniable agenda: To unreasonably manipulate our anxieties and fears; to sadistically tease and tweak our nerves, brains, and sweat glands; to engage our panic reflex as often and as violently as possible; to keep us squirming in our seats and leave us breathless by the credits; to make the movie theatre as claustrophobic and uncomfortable as the inside of a pine box.

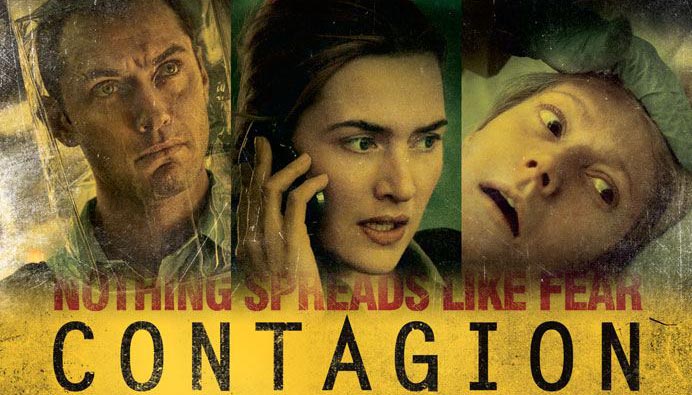

With Contagion, Steven (Oceans 11) Soderbergh commits to accomplish said goal by returning to an old stand-by of the genre: The unstoppable killer virus movie – where a bacterial menace is spreading undetectable and out of control.

It’s hard not to immediately hearken back to Wolfgang Petersen’s 1995 heart-pounder, Outbreak, the last major pandemic film with a stellar cast. There, Dustin Hoffman, Rene Russo, and Morgan Freeman raced to save lives and hold together the fabric of society as a cute little monkey (and a not so cute Patrick Dempsey) endangered millions. But even more recently, we had Julianne Moore in Blindness where the inability to see could be passed along like a viral plague. And, in a way, the popular spate of zombie movies (from 18 Days Later to I Am Legend to Zombieland) utilize a similar mechanism and play off the same trepidation we harbor to, without fault, catch something deadly. The villain in all these scenarios is all the more frightening because it is not implicitly evil; it is indifferent, without conscience, and cannot be reasoned with. In all such Thrillers, the aim for anyone as yet infected is to either remain that way until the antigen is discovered (and administered) or learn that they are miraculously immune, and survive.

I honestly can’t think of a single movie under this subcategory that was not at the very least compelling. The ingredients are just too provocative to fall flat. Soderbergh, who is as skilled as they come at uplifting routine templates (Joel and Ethan Coen are equally masterful), gives the infection movie über-A-list treatment. Beyond the remarkable star-power assembled to show the director support (Matt Damon, Gwyneth Paltrow, Jude Law, and Kate Winslet to name a few), Contagion gives the nightmare situation important, political, scientifically correct treatment. We know this is a movie of substance not only due to the international cast and exotic locales, but because those that we think cannot die – are, as we might imagine, narratively immune – do get sick and do die, and in inglorious, pathetic red-shirt ways no less. Contagion declares that such is the savagery of life and so is the merciless nature of, well, nature.

Contagion replaces Outbreak’s monkey with a bat and a pig, an irresponsible Patrick Dempsey with an unfaithful Gwyneth Paltrow, and a military/quarantine concentration with a research/pathology one. Both films are sophisticated enough to know that without a human element all the elaborate chaos and misery would remain unmoving, so writer Scott Z. Burns relates the global crisis by focusing on individuals playing crucial roles in either stopping, being victimized by, or profiting from the virus.

Although every film should be judged on its own merits, I continue to compare Soderberghs’s work to Petersen’s because outside of the contemporary cast, Contagion, as intense and sharp as it is, never really emerges from its predecessor’s shadow. The independent film pioneer Steven Soderbergh seems content here to let the infallible material do the heavy lifting for him.

If Contagion is an update of a common theme, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is as familiar and reliable as the old Barcalounger. Tomas Alfredson’s movie is about as straightforward a suspense flick as they come. It chisels together a maze made up of suave, icy Brits, worldwide espionage, double agents, and enough twists and turns to make Chubby Checker dizzy. Based on the John le Carre novel (one of three in a series), the film expertly unspools the tale of a bloody mess at the Secret Intelligence Service, England’s exclusive, elite cabal of foreign affairs agents. These men, portrayed with dry and scaly to the point of molting performances by the intimidating likes of John Hurt, Ciaràan Hinds, Colin Firth, and Gary Oldman, capture a terrific 1970’s machismo and chauvinism that has disappeared from the world.

At the heart of the film (adapted by Bridget O’Connor and Peter Straughan) is Gary Oldman’s Smiley (who does resemble an old man, but by no means smiley). The character is a composed and constricted company man who puts loyalty to her majesty the Queen and country above all else (and Oldman’s subtle, felt work exhibiting the bottled pain and frustration that goes along with such a lifestyle has and will continue to garner awards consideration). He is charged with looking for a spy within his own rank. We follow him into the shadows and records rooms and tight spots hoping that he (and we) are not discovered (and equally hoping that Smiley is not revealed to be our man). Alfredson knows how to wring the proper amount of suspense from each set up without stumbling over the edge. The coded jargon employed by our agents is precise and never defined, as it is up to us to pay close attention, become accustomed to it, and gradually join the fraternity. Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is not a film you can nod off on. The information required to solve the case – complicated, intricate, and dense – comes in downloadable segments compromised mainly of flashbacks and innuendo. Smiley is a dogged investigator, but he is not one for action or a witty comeback. He is more of a receptacle.

At the heart of the film (adapted by Bridget O’Connor and Peter Straughan) is Gary Oldman’s Smiley (who does resemble an old man, but by no means smiley). The character is a composed and constricted company man who puts loyalty to her majesty the Queen and country above all else (and Oldman’s subtle, felt work exhibiting the bottled pain and frustration that goes along with such a lifestyle has and will continue to garner awards consideration). He is charged with looking for a spy within his own rank. We follow him into the shadows and records rooms and tight spots hoping that he (and we) are not discovered (and equally hoping that Smiley is not revealed to be our man). Alfredson knows how to wring the proper amount of suspense from each set up without stumbling over the edge. The coded jargon employed by our agents is precise and never defined, as it is up to us to pay close attention, become accustomed to it, and gradually join the fraternity. Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is not a film you can nod off on. The information required to solve the case – complicated, intricate, and dense – comes in downloadable segments compromised mainly of flashbacks and innuendo. Smiley is a dogged investigator, but he is not one for action or a witty comeback. He is more of a receptacle.

At the end of the day, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is somberly amusing; it is intriguing – it is not thrilling. With the exception of one agent, the men of SIS are too politely vile for anyone to really care about their fate. We pity Smiley; we do not root for him (though we do root against almost everyone else on screen). Let these doughy pills take turns playing war games and stabbing each other in the back for eternity. Criticizing or belittling the film is sort of like taking issue with a cup of tea or a navy business suit from Men’s Warehouse. There is nothing sexy or exciting about these items, but they dutifully perform the task.

The one rogue member of the squad who actually does deserve audience compassion is named Rikki Tarr and portrayed by burgeoning talent Tom Hardy. The reason we are sympathetic toward Tarr is the same reason he does not fit into the SIS mold (and the same reason he is the bane of their existences). Tarr is wrestling with his humanity while being part of a service that recoils from such frailty. It is Tarr and his moments of weakness (if being human can be defined as such) that eventually brings down the house of cards.

Ironically, in Warrior, it is Hardy’s magnificent performance as someone who relinquishes (or, rather, was deprived of) his humanity that sets the tone for the drama and demands our emotional investment. Gavin O’Connor’s film about a high profile MMA tournament and the overlapping storylines leading to the final bout is undeniably exciting from a sensory vantage. There is no escaping the visceral impact of watching two physical specimens of muscle and sinew mercilessly collide to claim a multi million dollar prize.

Ironically, in Warrior, it is Hardy’s magnificent performance as someone who relinquishes (or, rather, was deprived of) his humanity that sets the tone for the drama and demands our emotional investment. Gavin O’Connor’s film about a high profile MMA tournament and the overlapping storylines leading to the final bout is undeniably exciting from a sensory vantage. There is no escaping the visceral impact of watching two physical specimens of muscle and sinew mercilessly collide to claim a multi million dollar prize.

O’Connor, who also contributed as writer and producer, took what Soderbergh perpetrated with Contagion and raised him one. Because as much as a movie can’t go wrong with a rampaging virus, the Rocky formula is about as foolproof as it gets. (O’Connor previously directed Miracle, about the ragtag U.S. hockey team that toppled the Soviet and Finnish titans at the 1980 Olympics). Warrior performs the same trick as Contagion in that it contemporizes the established formula. Instead of the old school boxing of Rocky (or the underground Kumite of Bloodsport, or the wrestling of Vision Quest, or the karate of The Karate Kid) we are shoved into the vicious arena of regulated mixed martial arts.

(I would be remiss if I did not note here that this year’s far less worthwhile Real Steel ventured the same trick by taking Rocky into the future with robot boxing).

Warrior does an admirable job separating itself from the fray of Rocky imitators not only by being the first mainstream film about MMA, but also by incorporating substantive musings on fatherhood and delving deep into family pathos.

Nick Nolte (his career still hanging in there) delivers stinging stuff as Paddy Conlon, a retired trainer trying to stay sober (as if there are any other kind) brought back into the game by his estranged son, Tommy (the petrifying hulk that is Tom Hardy), who has a lot of well-earned rage to vent. We are only given a sparing glimpse of that rage’s source, but clearly Paddy was a horrid, abusive father who tore his family apart.

If that were not enough (and I think it might have been) Tom is traumatized by his time in the Marine Corps where, we learn via a distracting aside, that he may have performed heroically…while going AWOL.

The best thing about Warrior (beyond the gift of superior acting) is that, unlike all prior incarnations of the recipe, O’Connor gives equal screen time to the gentleman on the other side of the fight card. Brendan Conlon (an authentic everyman Joel Edgerton) has reserved a spot in the tournament for assorted noble reasons including pride and mounting mortgage payments. If you have not guessed, Brendan and Tommy are brothers, though Brendan is well adjusted (yet perhaps equally damaged).

The writers (O’Connor along with Cliff Dorfman and Anthony Tambakis) are an ambitious trio and heap a lot onto their plates in the name of providing a rousing cinematic experience, however, it is often at the expense of credibility. Their script is prone to take the easy way out when fleshing out characters (for example, Brendan’s likeability is bolstered by his being a fun, smart beloved high school teacher – that way we get cheering teenagers in the finale), and though one cannot genuinely fault Warrior for the clichéd elements of its story, simply because reviving the cliché is the whole point, one can wish that the innovation evident was more consistent and fundamentally sound. It is where Warrior chooses the road less traveled that elevates it, but there are roads less traveled and then there are detours.

As another example, I respect O’Connor for paying sensitive attention to both “underdogs” who together wind up shocking the world. That was something new and brilliant. Why did they need to be brothers? Isn’t that contrivance a bit too far fetched? While it certainly added tension and made for a riveting title fight, it did so by needlessly straining the boundaries of possibility. Somehow, regardless of these stunts, the superior performances and confident direction convinces us of what we would otherwise deem impossible.

O’Connor clearly and capably crafted a film trying to avoid a by the numbers approach, and where a less motivated filmmaker would have faltered, his Warrior is a bruiser that refuses to tap out.

And for a good long exhilarating time, Joe Wright’s Hanna also seemed to be flipping the token thrill ride picture on its head (and snapping its neck in the process for good measure). Hanna, without exaggeration, opens with one of the most original, stunning, and suspenseful premises of any film that I can recall. There really is nothing like it, and therefore it is a damn shame when it eventually runs out of steam (i.e. creativity) and descends into lockstep with the clichés of the genre.

And isn’t that always the catch with so-called Thrillers? The set up is the easy part. Suspense is effortlessly generated by an unsolved crime, a flashlight in the gloom, an ancient curse, an ominous message, a new stranger in town. It is whether the writers can follow through and conjure up a satisfying payoff that determines if they earn their stripes.

And isn’t that always the catch with so-called Thrillers? The set up is the easy part. Suspense is effortlessly generated by an unsolved crime, a flashlight in the gloom, an ancient curse, an ominous message, a new stranger in town. It is whether the writers can follow through and conjure up a satisfying payoff that determines if they earn their stripes.

Hanna is all unanswered questions, veiled threats, and grave atmosphere as it begins in the frozen wilderness where a father (Eric Bana) and daughter, Hanna (Saoirse Ronan), maintain a spartan existence; hunting, training, preparing the soft-featured girl for something that she, like we, are in the dark about.

Once the chain of events is set into motion and the chase begins, we are treated to some great techno-fueled fight sequences and narrow escapes. The screenplay by David Farr and Seth Lochhead graciously chooses some evocative Southwestern landscapes to contrast with the snow covered prologue and the German albino looking and sounding Hanna. We even sort of get a road trip movie thrown into the mix.

Ms. Ronan is watchable and believable to the last drop in a demanding, complex role that has her challenged by adolescence as well as an ingrained propensity to murder and maim at will. Her nemesis, an ice queen with a formidable drawl played by Cate Blanchett (in campy Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull mode), will seemingly stop at nothing to study then destroy her. The ingredients are there for success, but as we build toward resolution (or even increased conflict) Hanna fails to develop at a rate to match the sum of its parts.

Much like Warrior, Hanna is trying to compensate for working within a recognizable framework. While both films add plot devices that ring contrived, only Warrior maintains a stable narrative frequency throughout. Before coming to an abrupt, indigestible halt, Hanna veers into science fiction terrain (Why is Hanna such a lethal weapon?) and then morphs into an unforgivably predictable B-level action flick. The biggest fall is for Blanchett, whose character seems to have a personality transplant mid-movie.

While I would argue that Wright got off to such a phenomenal start that it would have been difficult to keep up the breakneck (no pun intended) speed for the remainder of the movie, the laziness of the final act cannot be excused.

Hanna appeared at first to be a Thriller of exceptional genetic makeup, but it wound up just blossoming a bit premature.