ESPN reports on "The Hebrew Hammer" Dmitriy Salita. They say that while Dmitriys a great fighter, hes been fighting patsies. Dmitiry would love to fight big time fighters, but his managers want him to remain undefeated, in order keep his jewish hero status. Its time to let Dmitiry show what hes really capable of. We'll still love him if he loses against a top opponent. Give him a shot at the title.

Great Jewish Hope deserves a championship bout

By Jeff Pearlman

Special to Page 2

Four years ago, the whole Jewish thing made perfect sense.

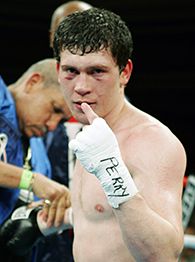

That was when I initially profiled Dmitriy Salita, a 20-year-old Brooklyn welterweight who was looking to break into the boxing mainstream. At the time, Salita was like a lot of other young pugilists attempting to rise through the ranks. He had quick hands, a powerful right cross, oodles of potential and an understandable need for a niche.

So, again, the whole Jewish thing made perfect sense. I still remember the day I first visited Dmitriy at his home in Flatbush. We hung out, talked a little, then walked over to a nearby Chabad House, where Salita entered through the back door, placed a yarmulke atop his head, opened a prayer book called Shma and wrapped the phylacteries — thin leather straps inscribed with Hebrew quotations — around his arm. For the ensuing half-hour he prayed silently.

The entire routine was anything but an act. Salita is a devoutly religious Jew, one who attends shul several times per week and knows in his heart what it is to be one of God's chosen people. His nickname is not "Killer" or "Blood Curdler," but "The Star of David." He enters the ring to Yiddish rap.

It was his goal to not only fight for himself, but for a religion that has often distanced itself from the sporting world. As a Jew myself, it was wonderful to see. Here was a man with righteous priorities. With a sense of being.

Fast forward four years, however, and there's a problem. On Thursday night, Salita will enter the ring at the Hammerstein Ballroom in New York to fight Grover Wiley.

I said … Grover Wiley!

GROVER WILEY, dammit!

That's right. You've never heard of Grover Wiley. Or, for that matter, Francisco Campos. Or Shad Howard. Or Robert Frankel. Or Shawn Gallegos. Or Louis Brown. Or Darelle Sukerow. Or Paul Delgado. Or Ruben Galvan. Or Ray Martinez. Or Frankie Sanchez. Or Richard Conchas. Or Verdell Smith. Or Joey Bartole. Or John Hoffman. Or Ryan Maraldo. Or Richard Ueding. Or Carlos Horacio Nevarez. Or Ron Gladden. Or Daniel Almanza. Or Arthur Medina. Or Jacob Godinez. Or Rashaan Abdul Blackburn. Or Miguel Mares. Or Nelson Valles. Or Joe Jiles. Or Robert Delgado. Or Larry Luftig.

OK, Larry Luftig is my next-door neighbor. But the rest are all real — the tin cans and inflatable dolls Salita has battered en route to a 26-0-1 record. This might read as a tad bit insulting to Dmitriy, but in a refreshing dose of athletic candor, the man sort of agrees. When we first met, Salita gave himself two years to line up a title fight. Two years came, two years went.

Salita battled every brawler who entered the ring without complaining. Now, frustration has set in.

"Sometimes it seems as if I'm allowed to smell a title opportunity, but I'm never allowed to touch it," he says. "There's been talk for a long time, but it's never materialized. I still keep the faith that an opportunity will come, but dealing with boxing is sometimes a science in and of itself."

In the weird world of pugilism, where promotional spark is three-quarters of the battle, I have a theory. As long as Salita remains undefeated, his handlers and matchmakers can assure themselves a gate by hyping the story line of Great Jewish Hope en route to the top. It's a guaranteed money maker: while Jewish people often struggle when it comes to slugging a baseball or dunking or knocking out a bully, we worship the chosen few among us who can. It's why, even if Shawn Green hits .220 for the Mets this season, he'll never have to worry about losing a core fan base. It's why former 49ers offensive lineman Harris Barton can walk into any Bay Area synagogue and be swarmed. It's why Perry Klein and Steve Ratzer and Steve Dubinsky — anonymous sports schlubs to 99.9 percent of America — maintain a special place in the hearts of Jewish die-hards. We loooooove our athletes.

Yet Salita has paid enough dues. He deserves more. When his parents, Alexander and Lyudmila, emigrated from the Ukrainian city of Odessa to Brooklyn 12 years ago, it was so their two children could live in a free country without the damnation of anti-Semitism.

"My mother and father wanted us to have a happy life," Salita said. "They didn't want us to feel ashamed of who we were."

Shortly after arriving in the U.S., Salita searched for nearby boxing gyms.

It was a journey he had wanted to make ever since he first saw "Rocky IV." Though in that film Rocky Balboa defeats Ivan Drago, Salita's (fictitious) fellow Soviet, the boy was smitten. By the film's end he was chanting "ROCK-EE! ROCK-EE!" and dreaming of his own title shot. When Salita entered Brooklyn's rough Starrett City Boxing Club for the first time, he was greeted by about 50 black and Latino fighters. He had found a home.

As Salita marched through the amateur ranks, putting together a 54-5 record and winning the 139-pound title at the 2001 New York Golden Gloves tournament, he was coming of age as a Jew. In 1997, Lyudmila had a recurrence of the breast cancer she had been diagnosed with in 1990, and Dmitriy sought comfort in his religion. In 1998, while visiting his mother in New York City's Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Dmitriy started talking to the husband of the woman in the bed next to his mother's. The man told Salita about the local Chabad center, and Dmitriy and his brother, Mikhail, began visiting there, praying for their mother's recovery.

By the time Lyudmila died in January 1999, Salita was so deeply committed to his religion that he refused to fight on the Sabbath — from Friday sundown until Saturday sundown.

It was a practice that at first turned off promoters, then excited them.

Salita was the real deal — a "Hebrew Hammer" who could draw the masses.

But now, it's time. When Salita inevitably defeats Wiley for his 27th win, he deserves — needs — a big fight. Give him Arturo Gatti. Give him Ricardo Torres. Heck, give him Ricky Hatton.

Yeah, maybe he'll lose.

But at least he'll no longer be Dmitriy Salita, the Jewish fighter.

He'll be Dmitriy Salita, the boxer.

Jeff Pearlman is a former Sports Illustrated senior writer and the author of "Love Me, Hate Me: Barry Bonds and the Making of an Antihero", now available in paperback. You can reach him at anngold22@yahoo.com.